Art of One Age That as So Defined the Characteristics of Human Beings That Is Can Speak

Anthropomorphism is the attribution of human being traits, emotions, or intentions to non-human being entities.[one] It is considered to be an innate tendency of human psychology.[ii]

Personification is the related attribution of human form and characteristics to abstract concepts such equally nations, emotions, and natural forces, such as seasons and weather condition.

Both take ancient roots every bit storytelling and creative devices, and most cultures have traditional fables with anthropomorphized animals as characters. People have also routinely attributed homo emotions and behavioral traits to wild equally well every bit domesticated animals.[iii]

Etymology

Anthropomorphism and anthropomorphization derive from the verb grade anthropomorphize,[a] itself derived from the Greek ánthrōpos ( ἄνθρωπος , lit. "human") and morphē ( μορφή , "grade"). Information technology is first attested in 1753, originally in reference to the heresy of applying a human being form to the Christian God.[b] [1]

Examples in prehistory

Anthropomorphic "pebble" figures from the 7th millennium BC

From the beginnings of homo behavioral modernity in the Upper Paleolithic, about 40,000 years ago, examples of zoomorphic (animal-shaped) works of fine art occur that may represent the earliest known evidence of anthropomorphism. 1 of the oldest known is an ivory sculpture, the Löwenmensch figurine, Deutschland, a human-shaped figurine with the head of a lioness or panthera leo, determined to be well-nigh 32,000 years old.[five] [6]

It is non possible to say what these prehistoric artworks stand for. A more recent case is The Sorcerer, an enigmatic cave painting from the Trois-Frères Cave, Ariège, France: the figure's significance is unknown, only it is usually interpreted as some kind of smashing spirit or master of the animals. In either case at that place is an element of anthropomorphism.

This anthropomorphic fine art has been linked past archaeologist Steven Mithen with the emergence of more systematic hunting practices in the Upper Palaeolithic.[7] He proposes that these are the product of a change in the architecture of the human listen, an increasing fluidity between the natural history and social intelligences [ description needed ], where anthropomorphism immune hunters to identify empathetically with hunted animals and better predict their movements.[c]

In faith and mythology

In religion and mythology, anthropomorphism is the perception of a divine being or beings in homo course, or the recognition of human being qualities in these beings.

Ancient mythologies frequently represented the divine as deities with human forms and qualities. They resemble human beings not simply in appearance and personality; they exhibited many human behaviors that were used to explain natural phenomena, creation, and historical events. The deities vicious in love, married, had children, fought battles, wielded weapons, and rode horses and chariots. They feasted on special foods, and sometimes required sacrifices of food, beverage, and sacred objects to be made by homo beings. Some anthropomorphic deities represented specific man concepts, such as love, war, fertility, beauty, or the seasons. Anthropomorphic deities exhibited human qualities such equally beauty, wisdom, and ability, and sometimes homo weaknesses such as greed, hatred, jealousy, and uncontrollable acrimony. Greek deities such as Zeus and Apollo frequently were depicted in man form exhibiting both commendable and despicable human traits. Anthropomorphism in this case is, more than specifically, anthropotheism.[ix]

From the perspective of adherents to religions in which humans were created in the course of the divine, the phenomenon may be considered theomorphism, or the giving of divine qualities to humans.

Anthropomorphism has cropped upward every bit a Christian heresy, peculiarly prominently with the Audians in third century Syria, only besides in fourth century Egypt and tenth century Italia.[x] This often was based on a literal interpretation of Genesis ane:27: "Then God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them".[eleven]

Criticism

Some religions, scholars, and philosophers objected to anthropomorphic deities. The earliest known criticism was that of the Greek philosopher Xenophanes (570–480 BCE) who observed that people model their gods after themselves. He argued against the conception of deities as fundamentally anthropomorphic:

Simply if cattle and horses and lions had hands

or could paint with their hands and create works such as men do,

horses similar horses and cattle like cattle

also would depict the gods' shapes and make their bodies

of such a sort as the form they themselves take.

...

Ethiopians say that their gods are snub–nosed [ σιμούς ] and black

Thracians that they are pale and red-haired.[12] [d]

Xenophanes said that "the greatest god" resembles man "neither in form nor in heed".[13]

Both Judaism and Islam pass up an anthropomorphic deity, believing that God is beyond human being comprehension. Judaism'due south rejection of an anthropomorphic deity grew during the Hasmonean period (circa 300 BCE), when Jewish conventionalities incorporated some Greek philosophy.[1] Judaism'south rejection grew further later on the Islamic Gilded Age in the 10th century, which Maimonides codification in the twelfth century, in his thirteen principles of Jewish religion.[e]

In the Ismaili interpretation of Islam, assigning attributes to God also as negating any attributes from God (via negativa) both authorize equally anthropomorphism and are rejected, as God cannot exist understood past either assigning attributes to Him or taking attributes abroad from Him. The 10th-century Ismaili philosopher Abu Yaqub al-Sijistani suggested the method of double negation; for example: "God is not real" followed by "God is non non-existent". This glorifies God from any agreement or human comprehension.[fifteen]

Hindus do not pass up the concept of a deity in the abstract unmanifested, but note practical problems. Lord Krishna said in the Bhagavad Gita, Chapter 12, Verse 5, that it is much more difficult for people to focus on a deity as the unmanifested than 1 with form, using anthropomorphic icons (murtis), because people need to perceive with their senses.[16] [17]

In secular thought, one of the most notable criticisms began in 1600 with Francis Bacon, who argued against Aristotle's teleology, which alleged that everything behaves every bit it does in order to achieve some end, in order to fulfill itself.[18] Bacon pointed out that achieving ends is a human activeness and to attribute it to nature misconstrues it as humanlike.[18] Modern criticisms followed Bacon's ideas such every bit critiques of Baruch Spinoza and David Hume. The latter, for instance, embedded his arguments in his wider criticism of human religions and specifically demonstrated in what he cited every bit their "inconsistence" where, on i hand, the Deity is painted in the most sublime colors but, on the other, is degraded to nearly human levels by giving him man infirmities, passions, and prejudices.[19] In Faces in the Clouds, anthropologist Stewart Guthrie proposes that all religions are anthropomorphisms that originate in the brain'southward tendency to detect the presence or vestiges of other humans in natural phenomena.[20]

There are also scholars who argue that anthropomorphism is the overestimation of the similarity of humans and nonhumans, therefore, it could non yield authentic accounts.[21]

In literature

Religious texts

There are various examples of personification in both the Hebrew Bible and Christian New Testaments, too as in the texts of some other religions.

Fables

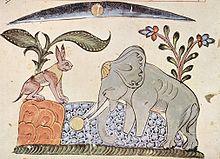

From the Panchatantra: Rabbit fools Elephant past showing the reflection of the moon

Anthropomorphism, also referred to as personification, is a well established literary device from ancient times. The story of "The Militarist and the Nightingale" in Hesiod's Works and Days preceded Aesop's fables past centuries. Collections of linked fables from India, the Jataka Tales and Panchatantra, also employ anthropomorphized animals to illustrate principles of life. Many of the stereotypes of animals that are recognized today, such as the wily fox and the proud king of beasts, can exist found in these collections. Aesop'southward anthropomorphisms were so familiar past the kickoff century CE that they colored the thinking of at to the lowest degree one philosopher:

And in that location is some other charm well-nigh him, namely, that he puts animals in a pleasing light and makes them interesting to mankind. For afterwards existence brought upward from childhood with these stories, and after being every bit it were nursed by them from babyhood, we larn sure opinions of the several animals and think of some of them as royal animals, of others as empty-headed, of others as witty, and others every bit innocent.

Apollonius noted that the legend was created to teach wisdom through fictions that are meant to exist taken as fictions, contrasting them favorably with the poets' stories of the deities that are sometimes taken literally. Aesop, "by announcing a story which anybody knows not to be true, told the truth by the very fact that he did non claim to be relating real events".[22] The same consciousness of the fable equally fiction is to exist found in other examples across the world, 1 example beingness a traditional Ashanti way of get-go tales of the anthropomorphic trickster-spider Anansi: "Nosotros practise not really mean, we practise not actually mean that what nosotros are about to say is true. A story, a story; permit it come, permit information technology go."[23]

Fairy tales

Anthropomorphic motifs have been common in fairy tales from the earliest aboriginal examples ready in a mythological context to the great collections of the Brothers Grimm and Perrault. The Tale of Two Brothers (Egypt, 13th century BCE) features several talking cows and in Cupid and Psyche (Rome, 2nd century CE) Zephyrus, the westward wind, carries Psyche abroad. Later an ant feels sorry for her and helps her in her quest.

Mod literature

From The Emperor's Rout (1831)

Building on the popularity of fables and fairy tales, children'due south literature began to emerge in the nineteenth century with works such as Alice'south Adventures in Wonderland (1865) past Lewis Carroll, The Adventures of Pinocchio (1883) by Carlo Collodi and The Jungle Book (1894) past Rudyard Kipling, all employing anthropomorphic elements. This continued in the twentieth century with many of the almost popular titles having anthropomorphic characters,[24] examples being The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1901) and later books by Beatrix Potter;[f] The Current of air in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame (1908); Winnie-the-Pooh (1926) and The House at Pooh Corner (1928) by A. A. Milne; and The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe (1950) and the subsequent books in The Chronicles of Narnia series by C. S. Lewis.

In many of these stories the animals can be seen as representing facets of man personality and character.[26] As John Rowe Townsend remarks, discussing The Jungle Book in which the male child Mowgli must rely on his new friends the bear Baloo and the blackness panther Bagheera, "The world of the jungle is in fact both itself and our world likewise".[26] A notable piece of work aimed at an adult audition is George Orwell's Fauna Farm, in which all the main characters are anthropomorphic animals. Non-animal examples include Rev.Westward Awdry's children'south stories of Thomas the Tank Engine and other anthropomorphic locomotives.

The fantasy genre developed from mythological, fairy tale, and Romance motifs[27] sometimes have anthropomorphic animals as characters. The best-selling examples of the genre are The Hobbit [28] (1937) and The Lord of the Rings [one thousand] (1954–1955), both by J. R. R. Tolkien, books peopled with talking creatures such equally ravens, spiders, and the dragon Smaug and a multitude of anthropomorphic goblins and elves. John D. Rateliff calls this the "Doctor Dolittle Theme" in his book The History of the Hobbit [30] and Tolkien saw this anthropomorphism as closely linked to the emergence of homo language and myth: "...The commencement men to talk of 'copse and stars' saw things very differently. To them, the globe was live with mythological beings... To them the whole of creation was 'myth-woven and elf-patterned'."[31]

Richard Adams developed a distinctive take on anthropomorphic writing in the 1970s: his debut novel, Watership Downward (1972), featured rabbits that could talk—with their own distinctive language (Lapine) and mythology—and included a police-state warren, Efrafa. Despite this, Adams attempted to ensure his characters' behavior mirrored that of wild rabbits, engaging in fighting, copulating and defecating, drawing on Ronald Lockley's report The Individual Life of the Rabbit equally research. Adams returned to anthropomorphic storytelling in his later novels The Plague Dogs (1977) and Traveller (1988).[32] [33]

By the 21st century, the children'due south picture volume market had expanded massively.[h] Maybe a majority of picture show books accept some kind of anthropomorphism,[24] [35] with popular examples beingness The Very Hungry Caterpillar (1969) past Eric Carle and The Gruffalo (1999) past Julia Donaldson.

Anthropomorphism in literature and other media led to a sub-civilisation known as furry fandom, which promotes and creates stories and artwork involving anthropomorphic animals, and the test and estimation of humanity through anthropomorphism. This tin often be shortened in searches as "anthro", used by some every bit an alternative term to "furry".[36]

Anthropomorphic characters take too been a staple of the comic book genre. The most prominent one was Neil Gaiman's the Sandman which had a huge impact on how characters that are concrete embodiments are written in the fantasy genre.[37] [38] Other examples as well include the mature Hellblazer (personified political and moral ideas), Fables and its spin-off series Jack of Fables, which was unique for having anthropomorphic representation of literary techniques and genres.[40] Diverse Japanese manga and anime accept used anthropomorphism every bit the basis of their story. Examples include Squid Girl (anthropomorphized squid), Hetalia: Centrality Powers (personified countries), Upotte!! (personified guns), Arpeggio of Blue Steel and Kancolle (personified ships).

In film

Large Buck Bunny is a free animated short featuring anthropomorphic characters

Some of the most notable examples are the Walt Disney characters the Magic Carpet from Disney's Aladdin franchise, Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, Goofy, and Oswald the Lucky Rabbit; the Looney Tunes characters Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, and Porky Pig; and an assortment of others from the 1920s to present solar day.

In the Disney/Pixar franchises Cars and Planes, all the characters are anthropomorphic vehicles,[41] while in Toy Story, they are anthropomorphic toys. Other Pixar franchises like Monsters, Inc. features anthropomorphic monsters, and Finding Nemo features anthropomorphic marine life creatures (like fish, sharks, and whales). Discussing anthropomorphic animals from DreamWorks franchise Madagascar, Laurie [ non sequitur ] suggests that "social differences based on conflict and contradiction are naturalized and made less 'contestable' through the classificatory matrix of human and nonhuman relations [ description needed ]".[41] Other DreamWorks franchises similar Shrek features fairy tale characters, and Bluish Sky Studios of 20th Century Fox franchises similar Water ice Historic period features anthropomorphic extinct animals.

All of the characters in Walt Disney Blitheness Studios' Zootopia (2016) are anthropomorphic animals, that is an entirely nonhuman civilization.[42]

The live-action/computer-blithe franchise Alvin and the Chipmunks by 20th Century Trick centers around anthropomorphic talkative and singing chipmunks. The female singing chipmunks called The Chipettes are also centered in some of the franchise's films.

In television

Since the 1960s, anthropomorphism has also been represented in various animated television set shows such every bit Biker Mice From Mars (1993–1996) and SWAT Kats: The Radical Squadron (1993–1995). Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, beginning aired in 1987, features four pizza-loving anthropomorphic turtles with a great knowledge of ninjutsu, led by their anthropomorphic rat sensei, Master Splinter. Nickelodeon'south longest running animated TV series SpongeBob SquarePants (1999–present), revolves around SpongeBob, a xanthous bounding main sponge, living in the underwater town of Bikini Bottom with his anthropomorphic marine life friends. Cartoon Network's animated series The Amazing Earth of Gumball (2011–2019) are about anthropomorphic animals and inanimate objects. All of the characters in Hasbro Studios' TV series My Little Pony: Friendship Is Magic (2010–2019) are anthropomorphic fantasy creatures, with nigh of them being ponies living in the pony-inhabited land of Equestria. The Netflix original serial Centaurworld focuses on a warhorse who gets transported to a Dr. Seuss-similar globe full of centaurs who possess the bottom one-half of whatever animate being, as opposed to the traditional horse.

In the American blithe TV series Family unit Guy, ane of the show's main characters, Brian, is a dog. Brian shows many human characteristics – he walks upright, talks, smokes, and drinks Martinis – but also acts like a normal canis familiaris in other ways; for instance he cannot resist chasing a ball and barks at the mailman, believing him to be a threat.

The PBS Kids animated series Let'due south Go Luna! centers on an anthropomorphic female Moon who speaks, sings, and dances. She comes downwardly out of the heaven to serve as a tutor of international civilization to the three main characters: a boy frog and wombat and a daughter butterfly, who are supposed to be preschool children traveling a world populated by anthropomorphic animals with a circus run past their parents.

The French-Belgian animated series Mush-Mush & the Mushables takes place in a world inhabited by Mushables, which are anthropomrphic fungi, forth with other critters such as beetles, snails, and frogs.

In video games

In Armello, anthropomorphic animals battle for control of the animal kingdom

Sonic the Hedgehog, a video game franchise debuting in 1991, features a speedy blueish hedgehog as the main protagonist. This series' characters are almost all anthropomorphic animals such as foxes, cats, and other hedgehogs who are able to speak and walk on their hind legs like normal humans. As with most anthropomorphisms of animals, clothing is of little or no importance, where some characters may be fully clothed while some wear only shoes and gloves.

Some other popular case in video games is the Super Mario series, debuting in 1985 with Super Mario Bros., of which main adversary includes a fictional species of anthropomorphic turtle-like creatures known as Koopas. Other games in the serial, besides as of other of its greater Mario franchise, spawned similar characters such as Yoshi, Donkey Kong and many others.

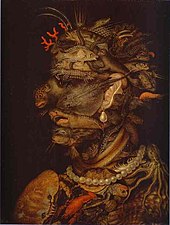

Art history

Claes Oldenburg

Claes Oldenburg'south soft sculptures are commonly described every bit anthropomorphic. Depicting common household objects, Oldenburg's sculptures were considered Popular Art. Reproducing these objects, often at a greater size than the original, Oldenburg created his sculptures out of soft materials. The anthropomorphic qualities of the sculptures were mainly in their sagging and malleable exterior which mirrored the non-and then-idealistic forms of the human body. In "Soft Light Switches" Oldenburg creates a household light switch out of vinyl. The two identical switches, in a dulled orange, allude nipples. The soft vinyl references the aging process as the sculpture wrinkles and sinks with fourth dimension.

Minimalism

In the essay "Art and Objecthood", Michael Fried makes the example that "literalist art" (minimalism) becomes theatrical by means of anthropomorphism. The viewer engages the minimalist work, not as an autonomous art object, only equally a theatrical interaction. Fried references a conversation in which Tony Smith answers questions about his vi-pes cube, "Die".

Q: Why didn't yous brand information technology larger so that it would loom over the observer?

A: I was non making a monument.

Q: Then why didn't you make it smaller and so that the observer could run across over the top?

A: I was not making an object.

Fried implies an anthropomorphic connection by means of "a surrogate person – that is, a kind of statue."

The minimalist conclusion of "hollowness" in much of their work was also considered by Fried to be "blatantly anthropomorphic". This "hollowness" contributes to the thought of a carve up within; an idea mirrored in the human course. Fried considers the Literalist art's "hollowness" to exist "biomorphic" as it references a living organism.[43]

Post-minimalism

Curator Lucy Lippard'due south Eccentric Abstraction show, in 1966, sets upwards Briony Fer'due south writing of a post-minimalist anthropomorphism. Reacting to Fried'southward interpretation of minimalist art's "looming presence of objects which appear as actors might on a phase", Fer interprets the artists in Eccentric Abstraction to a new grade of anthropomorphism. She puts forth the thoughts of Surrealist writer Roger Caillois, who speaks of the "spacial lure of the subject, the style in which the subject could inhabit their surround." Caillous uses the example of an insect who "through cover-up does then in order to become invisible... and loses its distinctness." For Fer, the anthropomorphic qualities of imitation found in the erotic, organic sculptures of artists Eva Hesse and Louise Bourgeois, are not necessarily for strictly "mimetic" purposes. Instead, like the insect, the piece of work must come into being in the "scopic field... which we cannot view from exterior."[44]

Mascots

For branding, merchandising, and representation, figures known as mascots are now ofttimes employed to personify sports teams, corporations, and major events such as the World'south Fair and the Olympics. These personifications may be simple homo or beast figures, such equally Ronald McDonald or the donkey that represents the United states's Democratic Party. Other times, they are anthropomorphic items, such as "Clippy" or the "Michelin Human". Most oftentimes, they are anthropomorphic animals such as the Energizer Bunny or the San Diego Chicken.

The practice is particularly widespread in Nihon, where cities, regions, and companies all have mascots, collectively known as yuru-chara. Ii of the most pop are Kumamon (a comport who represents Kumamoto Prefecture)[45] and Funassyi (a pear who represents Funabashi, a suburb of Tokyo).[46]

Animals

| | This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to information technology. (July 2016) |

Other examples of anthropomorphism include the attribution of homo traits to animals, especially domesticated pets such as dogs and cats. Examples of this include thinking a dog is smiling just because it is showing his teeth,[47] or a true cat mourns for a dead owner.[48] Anthropomorphism may be benign to the welfare of animals. A 2012 study by Butterfield et al. constitute that utilizing anthropomorphic language when describing dogs created a greater willingness to help them in situations of distress.[49] Previous studies have shown that individuals who attribute human characteristics to animals are less willing to consume them,[50] and that the degree to which individuals perceive minds in other animals predicts the moral business afforded to them.[51] It is possible that anthropomorphism leads humans to like non-humans more when they accept apparent man qualities, since perceived similarity has been shown to increase prosocial behavior toward other humans.[52]

In science

In scientific discipline, the use of anthropomorphic language that suggests animals take intentions and emotions has traditionally been deprecated as indicating a lack of objectivity. Biologists have been warned to avert assumptions that animals share any of the same mental, social, and emotional capacities of humans, and to rely instead on strictly observable evidence.[53] In 1927 Ivan Pavlov wrote that animals should be considered "without any need to resort to fantastic speculations every bit to the existence of any possible subjective states".[54] More than recently, The Oxford companion to animate being behaviour (1987) brash that "i is well brash to report the behaviour rather than attempting to get at whatever underlying emotion".[55] Some scientists, like William M Wheeler (writing apologetically of his utilize of anthropomorphism in 1911), have used anthropomorphic linguistic communication in metaphor to make subjects more humanly comprehensible or memorable.[i]

Despite the impact of Charles Darwin'south ideas in The Expression of the Emotions in Homo and Animals (Konrad Lorenz in 1965 called him a "patron saint" of ethology)[57] ethology has by and large focused on behavior, not on emotion in animals.[57]

Even insects play together, equally has been described by that excellent observer, P. Huber, who saw ants chasing and pretending to bite each other, like and then many puppies.

The study of corking apes in their ain surround and in captivity[j] has inverse attitudes to anthropomorphism. In the 1960s the iii so-called "Leakey'south Angels", Jane Goodall studying chimpanzees, Dian Fossey studying gorillas and Biruté Galdikas studying orangutans, were all accused of "that worst of ethological sins – anthropomorphism".[60] The accuse was brought well-nigh by their descriptions of the keen apes in the field; it is now more widely accepted that empathy has an important part to play in enquiry.

De Waal has written: "To endow animals with man emotions has long been a scientific taboo. But if nosotros practice not, we run a risk missing something fundamental, about both animals and united states."[61] Alongside this has come increasing awareness of the linguistic abilities of the great apes and the recognition that they are tool-makers and have individuality and culture.[62]

Writing of cats in 1992, veterinarian Bruce Fogle points to the fact that "both humans and cats take identical neurochemicals and regions in the encephalon responsible for emotion" as testify that "it is not anthropomorphic to credit cats with emotions such as jealousy".[63]

In calculating

In science fiction, an artificially-intelligent computer or robot, even though it has not been programmed with human emotions, ofttimes spontaneously experiences those emotions anyway: for case, Amanuensis Smith in The Matrix was influenced by a "disgust" toward humanity. This is an case of anthropomorphism: in reality, while an bogus intelligence could maybe be deliberately programmed with man emotions, or could develop something similar to an emotion as a means to an ultimate goal if it is useful to do and then, it would non spontaneously develop human emotions for no purpose whatsoever, as portrayed in fiction.[64]

One instance of anthropomorphism would be to believe that one'southward computer is aroused at them considering they insulted it; some other would be to believe that an intelligent robot would naturally detect a woman attractive and be driven to mate with her. Scholars sometimes disagree with each other most whether a particular prediction nearly an artificial intelligence's behavior is logical, or whether the prediction constitutes illogical anthropomorphism.[64] An instance that might initially exist considered anthropomorphism, only is in fact a logical statement about an artificial intelligence'south behavior, would be the Dario Floreano experiments where sure robots spontaneously evolved a rough chapters for "charade", and tricked other robots into eating "poisonous substance" and dying: hither, a trait, "deception", ordinarily associated with people rather than with machines, spontaneously evolves in a type of convergent evolution.[65]

The conscious use of anthropomorphic metaphor is not intrinsically unwise; ascribing mental processes to the computer, nether the proper circumstances, may serve the same purpose equally it does when humans do it to other people: information technology may help persons to empathize what the computer will practise, how their deportment will bear upon the computer, how to compare computers with humans, and conceivably how to design computer programs. Even so, inappropriate use of anthropomorphic metaphors can outcome in false behavior about the beliefs of computers, for case by causing people to overestimate how "flexible" computers are.[66] According to Paul R. Cohen and Edward Feigenbaum, in order to differentiate between anthropomorphization and logical prediction of AI behavior, "the trick is to know enough about how humans and computers call up to say exactly what they accept in common, and, when we lack this noesis, to use the comparison to advise theories of human thinking or computer thinking."[67]

Computers overturn the babyhood hierarchical taxonomy of "stones (non-living) → plants (living) → animals (conscious) → humans (rational)", past introducing a non-human "actor" that appears to regularly conduct rationally. Much of calculating terminology derives from anthropomorphic metaphors: computers tin can "read", "write", or "catch a virus". Information technology presents no clear correspondence with any other entities in the world besides humans; the options are either to leverage an emotional, imprecise human metaphor, or to decline imprecise metaphor and brand use of more than precise, domain-specific technical terms.[66]

People often grant an unnecessary social role to computers during interactions. The underlying causes are debated; Youngme Moon and Clifford Nass propose that humans are emotionally, intellectually and physiologically biased toward social activity, and and then when presented with even tiny social cues, deeply-infused social responses are triggered automatically.[66] [68] This may allow incorporation of anthropomorphic features into computers/robots to enable more than familiar "social" interactions, making them easier to use.[69]

Psychology

Foundational enquiry

In psychology, the first empirical report of anthropomorphism was conducted in 1944 by Fritz Heider and Marianne Simmel.[70] In the first part of this experiment, the researchers showed a 2-and-a-one-half minute long animation of several shapes moving effectually on the screen in varying directions at various speeds. When subjects were asked to describe what they saw, they gave detailed accounts of the intentions and personalities of the shapes. For instance, the big triangle was characterized as a dandy, chasing the other two shapes until they could trick the large triangle and escape. The researchers concluded that when people meet objects making motions for which there is no obvious cause, they view these objects as intentional agents (individuals that deliberately make choices to reach goals).

Modern psychologists generally characterize anthropomorphism as a cognitive bias. That is, anthropomorphism is a cerebral process by which people use their schemas almost other humans as a basis for inferring the properties of non-man entities in lodge to make efficient judgements about the environment, even if those inferences are non always accurate.[2] Schemas near humans are used as the footing because this cognition is caused early in life, is more detailed than cognition virtually non-human being entities, and is more readily accessible in retentiveness.[71] Anthropomorphism can besides part as a strategy to cope with loneliness when other homo connections are not available.[72]

3-factor theory

Since making inferences requires cerebral effort, anthropomorphism is probable to be triggered merely when certain aspects about a person and their environment are true. Psychologist Adam Waytz and his colleagues created a three-factor theory of anthropomorphism to describe these aspects and predict when people are well-nigh probable to anthropomorphize.[71] The 3 factors are:

- Elicited amanuensis knowledge, or the amount of prior cognition held about an object and the extent to which that knowledge is called to mind.

- Effectance, or the drive to interact with and understand ane's surround.

- Sociality, the need to establish social connections.

When elicited agent knowledge is low and effectance and sociality are loftier, people are more probable to anthropomorphize. Diverse dispositional, situational, developmental, and cultural variables can bear upon these three factors, such as need for knowledge, social disconnection, cultural ideologies, uncertainty avoidance, etc.

Developmental perspective

Children appear to anthropomorphize and utilize egocentric reasoning from an early on age and use it more frequently than adults.[73] Examples of this are describing a storm cloud as "aroused" or drawing flowers with faces. This penchant for anthropomorphism is likely because children have acquired vast amounts of socialization, only not as much experience with specific non-human being entities, so thus they have less adult culling schemas for their environment.[71] In contrast, autistic children tend to draw anthropomorphized objects in purely mechanical terms (that is, in terms of what they do) because they have difficulties with theory of heed.[74]

Consequence on learning

Anthropomorphism can be used to help learning. Specifically, anthropomorphized words[75] and describing scientific concepts with intentionality[76] tin improve afterwards recall of these concepts.

In mental health

In people with depression, social anxiety, or other mental illnesses, emotional support animals are a useful component of handling partially because anthropomorphism of these animals can satisfy the patients' need for social connection.[77]

In marketing

Anthropomorphism of inanimate objects can affect product ownership behavior. When products seem to resemble a man schema, such as the front of a automobile resembling a face, potential buyers evaluate that product more than positively than if they practice not anthropomorphize the object.[78]

People too tend to trust robots to do more than complex tasks such as driving a car or childcare if the robot resembles humans in means such as having a face, voice, and name; mimicking human motions; expressing emotion; and displaying some variability in behavior.[79] [80]

Image gallery

-

Danish electrical socket

See too

- Aniconism – antithetic concept

- Animism

- Anthropic principle

- Anthropocentrism

- Anthropology

- Anthropomorphic maps

- Anthropopathism

- Cynocephaly

- Furry fandom

- Peachy Concatenation of Existence

- Human-animal hybrid

- Humanoid

- Moe anthropomorphism

- National personification

- Pareidolia – seeing faces in everyday objects

- Pathetic fallacy

- Prosopopoeia

- Speciesism

- Talking animals in fiction

- Tashbih

- Zoomorphism

Notes

- ^ Possibly via French anthropomorphisme .[1]

- ^ Anthropomorphism, among divines, the error of those who ascribe a homo figure to the deity.[four]

- ^ In the New York Review of Books, Gardner opined that "I find near convincing Mithen's claim that human intelligence lies in the capacity to make connections: through using metaphors".[8]

- ^ Many other translations of this passage have Xenophanes land that the Thracians were "blond".

- ^ Moses Maimonides quoted Rabbi Abraham Ben David: "It is stated in the Torah and books of the prophets that God has no body, as stated 'Since K-d your God is the god (lit. gods) in the heavens above and in the world below" and a body cannot be in both places. And information technology was said 'Since you have not seen any prototype' and it was said 'To who would you compare me, and I would be equal to them?' and if he was a body, he would exist similar the other bodies."[14]

- ^ The Victoria and Albert Museum wrote: "Beatrix Potter is nevertheless i of the earth's acknowledged and best-loved children's authors. Potter wrote and illustrated a full of 28 books, including the 23 Tales, the 'little books' that have been translated into more than 35 languages and sold over 100 million copies."[25]

- ^ 150 million sold, a 2007 estimate of copies of the full story sold, whether published as one volume, 3, or some other configuration.[29]

- ^ Information technology is estimated that the Great britain market for children's books was worth £672m in 2004.[34]

- ^ In 1911, Wheeler wrote: "The larval insect is, if I may exist permitted to lapse for a moment into anthropomorphism, a sluggish, greedy, self-centred animate being, while the adult is industrious, abstinent and highly donating..."[56]

- ^ In 1946, Hebb wrote: "A thoroughgoing attempt to avert anthropomorphic description in the study of temperament was made over a two-twelvemonth flow at the Yerkes laboratories. All that resulted was an most endless series of specific acts in which no order or significant could be found. On the other mitt, by the use of frankly anthropomorphic concepts of emotion and attitude one could quickly and easily describe the peculiarities of individual animals... Any the anthropomorphic terminology may seem to imply about witting states in chimpanzee, information technology provides an intelligible and practical guide to behavior."[59]

References

- ^ a b c Oxford English Dictionary, 1st ed. "anthropomorphism, n." Oxford University Printing (Oxford), 1885.

- ^ a b Hutson, Matthew (2012). The 7 Laws of Magical Thinking: How Irrational Beliefs Continue U.s. Happy, Healthy, and Sane. New York: Hudson Street Press. pp. 165–81. ISBN978-i-101-55832-4.

- ^ Moss, Stephen (xv Jan 2016). "What yous see in this picture says more than almost you than the kangaroo". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 18 September 2019. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ^ Chambers's Cyclopædia, Supplement, 1753

- ^ "Lionheaded Figurine". Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ^ Dalton (1 January 2004). "Löwenmensch Oldest Statue". VNN World. Archived from the original on 25 March 2010.

- ^ Mithen 1998.

- ^ Gardner, Howard (nine October 1997), "Thinking Almost Thinking", New York Review of Books, archived from the original on 29 March 2010, retrieved 8 May 2010

- ^ "anthropotheism". Ologies & -Isms. The Gale Group, Inc. 2008. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 23 August 2009.

- ^ Play tricks, James Joseph (1907). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^

Chambers, Ephraim, ed. (1728). "Anthropomorphite". Cyclopædia, or an Universal Lexicon of Arts and Sciences (1st ed.). James and John Knapton, et al.

Chambers, Ephraim, ed. (1728). "Anthropomorphite". Cyclopædia, or an Universal Lexicon of Arts and Sciences (1st ed.). James and John Knapton, et al. - ^ Diels-Kranz, Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker, Xenophanes frr. 15–16.

- ^ Cloudless of Alexandria, Miscellanies V xiv 109.1–3

- ^ Maimonides, Moses, "Fundamentals of Torah, Ch. 1, § 8", Book of Science

- ^ Virani, Shafique N. (2010). "The Correct Path: A Post-Mongol Persian Ismaili Treatise". Iranian Studies. 43 (2): 197–221. doi:ten.1080/00210860903541988. ISSN 0021-0862. S2CID 170748666. Archived from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ Fowler, Jeanne D. (1997). Hinduism: Beliefs and Practices. Sussex Bookish Press. pp. 42–43. ISBN978-1898723608.

- ^ Narayan, 1000. K. Five. (2007). Flipside of Hindu Symbolism. Fultus. pp. 84–85. ISBN978-1596821170. Archived from the original on xiii Baronial 2021. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ a b Mitchell, Robert; Thompson, Nicholas; Miles, Lyn (1997). Anthropomorphism, Anecdotes, and Animals . New York: Land Academy of New York Press. pp. 51. ISBN978-0791431252.

- ^ Bailey, Alan; O'Brien, Dan (2014). Hume's Critique of Faith: 'Sick Men's Dreams' . Dordrecht: Springer Science+Business Media. p. 172. ISBN9789400766143.

- ^ Guthrie, Stewart E. (1995). Faces in the Clouds: A New Theory of Religion. Oxford Academy Press. p. seven. ISBN978-0-nineteen-509891-iv. Archived from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved eight November 2020.

- ^ Armstrong, Susan; Botzler, Richard (2016). The Animal Ideals Reader, tertiary edition. Oxon: Routledge. p. 91. ISBN9781138918009.

- ^ a b Philostratus, Flavius (c. 210 CE). The Life of Apollonius Archived three March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, 5.14. Translated by F.C. Conybeare. the Loeb Classical Library (1912)

- ^ Kwesi Yankah (1983). "The Akan Trickster Cycle: Myth or Folktale?" (PDF). Trinidad University of the West Indies. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 December 2008. Retrieved vi May 2010.

- ^ a b "The pinnacle 50 children's books". The Telegraph. 22 February 2008. Archived from the original on 6 December 2019. Retrieved 2 April 2018. and Sophie Borland (22 February 2008). "Narnia triumphs over Harry Potter". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 6 December 2019. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "Beatrix Potter", Official website , Victoria and Albert Museum, archived from the original on 23 February 2011, retrieved 2 June 2010

- ^ a b Risk, Nikki; Yates, Sally (2008). Exploring Children'southward Literature. Sage Publications Ltd. ISBN978-1-4129-3013-0.

- ^ John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, p 621, ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ^ 100 million copies sold: BBC Archived 12 May 2011 at the Wayback Auto: Tolkien's memorabilia get on auction. eighteen March 2008

- ^ The Toronto Star, xvi Apr 2007, archived from the original on 9 March 2011, retrieved 24 August 2017

- ^ Rateliff, John D. (2007). The History of the Hobbit: Return to Bag-end. London: HarperCollins. p. 654. ISBN978-0-00-723555-ane.

- ^ Carpenter, Humphrey (1979). The Inklings: C. South. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, Charles Williams and Their Friends . Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p. 43. ISBN978-0-395-27628-0.

- ^ Pallardy, Richard (xiv January 2016). "Richard Adams". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Chicago, IL: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ Levy, Keren (19 December 2013). "Watership Down by Richard Adams: A tale of backbone, loyalty, language". theguardian.com. Archived from the original on xx August 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ "The Value of the Children's Picture show Volume Market" , 9 November 2005, archived from the original on ix June 2016

{{commendation}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Ben Myers (x June 2008). "Why nosotros're all animal lovers". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ Patten, Fred (2006). Furry! The World'due south All-time Anthropomorphic Fiction. ibooks. pp. 427–436. ISBN978-one-59687-319-3.

- ^ Buxton, Marc (thirty October 2013). "The Sandman: The Essential Horror Comic of the Nineties". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on iii November 2013.

- ^ Buxton, Marc (26 Jan 2014). "Past Crom! The x Greatest Fantasy Comics of All-Fourth dimension". Comic Book Resource. Archived from the original on 9 April 2014. Archive requires scrolldown

- ^ Doctorow, Cory (25 March 2010). "Great Fables Crossover: Fables goes fifty-fifty more than meta, stays just every bit rollicking". Boing. Archived from the original on 2 March 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ^ a b Laurie, Timothy (2015), "Condign-Animal Is A Trap For Humans", Deleuze and the Non-Homo, archived from the original on xiii August 2021, retrieved 23 June 2015 eds. Hannah Stark and Jon Roffe.

- ^ McNary, Dave (11 June 2015). "Watch: Disney'southward 'Zootopia' Trailer Introduces Animal-Run World". Variety. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ Fried, Michael (1998). Art and Objecthood. Chicago: University of Chicago Printing. ISBN978-0-226-26319-9.

- ^ Fer, Briony (1999). "Objects Beyond Objecthood". Oxford Art Journal. 22 (two): 25–36. doi:x.1093/oxartj/22.2.25.

- ^ Official website , archived from the original on 20 Apr 2021, retrieved 9 August 2015 . (in Japanese)

- ^ Official website , archived from the original on 7 January 2014, retrieved nine August 2015 . (in Japanese)

- ^ Woods, John (28 September 2018). "Do Dogs Really Smiling? The Science Explained". AllThingsDogs. Archived from the original on eleven Apr 2021. Retrieved eighteen March 2021.

- ^ Filion, Daniel. "Anthropomorphism: when we dear our pets too much". Educator. Archived from the original on iv March 2021. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ Butterfield, M. E.; Colina, S. E.; Lord, C. G. (2012). "Mangy mutt or furry friend? Anthropomorphism promotes animal welfare". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 48 (four): 957–960. doi:ten.1016/j.jesp.2012.02.010.

- ^ Bastian, B.; Loughnan, S.; Haslam, Northward.; Radke, H. R. (2012). "Don't mind meat? The denial of mind to animals used for man consumption". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 38 (2): 247–256. doi:10.1177/0146167211424291. PMID 21980158. S2CID 22757046.

- ^ Gray, H. M.; Gray, K.; Wegner, D. 1000. (2007). "Dimensions of Heed Perception". Science. 315 (5812): 619. Bibcode:2007Sci...315..619G. doi:ten.1126/science.1134475. PMID 17272713. S2CID 31773170.

- ^ Burger, J. M.; Messian, N.; Patel, Due south.; del Prado, A.; Anderson, C. (2004). "What a coincidence! The effects of incidental similarity on compliance". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 30 (one): 35–43. doi:10.1177/0146167203258838. PMID 15030641. S2CID 2109021.

- ^ Shapiro, Kenneth J. (1993). "Editor'southward Introduction to Society and Animals". Society & Animals. i (one): ane–4. doi:x.1163/156853093X00091. Afterward re-published as an introduction to: Flynn, Cliff (2008). Social Creatures: A Man and Brute Studies Reader. Lantern Books. ISBN978-i-59056-123-2. Archived from the original on eighteen May 2019. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ^ Ryder, Richard. Animal Revolution: Changing Attitudes Towards Speciesism. Berg, 2000, p. 6.

- ^ Masson & McCarthy 1996, p. 18.

- ^ Wheeler, William Morton (November 1911), "Insect parasitism and its peculiarities", Popular Scientific discipline, Vol. 79 , p. 443

- ^ a b Black, J (June 2002). "Darwin in the world of emotions". Journal of the Royal Order of Medicine. 95 (vi): 311–3. doi:10.1258/jrsm.95.half-dozen.311. ISSN 0141-0768. PMC1279921. PMID 12042386.

- ^ Darwin, Charles (1871). The Descent of Man (1st ed.). p. 39. Archived from the original on 12 July 2011. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ^ Hebb, Donald O. (1946), "Emotion in man and animal: An analysis of the intuitive processes of recognition", Psychological Review, 53 (2): 88–106, doi:x.1037/h0063033, PMID 21023321

- ^ Masson & McCarthy 1996, p. ix

- ^ Frans de Waal (1997-07). "Are Nosotros in Anthropodenial?" Archived 2 December 2019 at the Wayback Auto. Discover. pp. 50–53.

- ^ Whiten, Andrew (25 July 2017). "Culture extends the scope of evolutionary biology in the great apes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (30): 7790–7797. doi:10.1073/pnas.1620733114. PMC5544264. PMID 28739927.

- ^ Fogle, Bruce (1992). If Your Cat Could Talk. London: Dorling Kindersley. p. 11. ISBN9781405319867. Archived from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ a b Yudkowsky, Eliezer. "Artificial intelligence equally a positive and negative factor in global risk." Archived two March 2013 at the Wayback Machine Global catastrophic risks (2008).

- ^ "Real-Life Decepticons: Robots Larn to Cheat". Wired magazine. 18 August 2009. Archived from the original on 7 February 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ a b c Marakas, George Grand.; Johnson, Richard D.; Palmer, Jonathan West. (Apr 2000). "A theoretical model of differential social attributions toward computing technology: when the metaphor becomes the model". International Journal of Man-Computer Studies. 52 (4): 719–750. doi:10.1006/ijhc.1999.0348.

- ^ Cohen, Paul R., and Edward A. Feigenbaum, eds. The handbook of artificial intelligence. Vol. iii. Butterworth-Heinemann, 2014.

- ^ Moon, Youngme, and Clifford Nass. "How 'real' are computer personalities? Psychological responses to personality types in human-computer interaction." Communication inquiry 23.6 (1996): 651–674.

- ^ Duffy, Brian R. (March 2003). "Anthropomorphism and the social robot". Robotics and Autonomous Systems. 42 (3–4): 177–190. CiteSeerX10.1.1.59.9969. doi:10.1016/S0921-8890(02)00374-3.

- ^ "Fritz Heider & Marianne Simmel: An Experimental Report of Credible Behavior". Psychology. Archived from the original on 10 Dec 2015. Retrieved 16 Nov 2015.

- ^ a b c Epley, Nicholas; Waytz, Adam; Cacioppo, John T. (2007). "On seeing homo: A 3-factor theory of anthropomorphism". Psychological Review. 114 (4): 864–886. CiteSeerX10.1.1.457.4031. doi:ten.1037/0033-295x.114.4.864. PMID 17907867.

- ^ Waytz, Adam (2013). "Social Connexion and Seeing Homo – Oxford Handbooks". The Oxford Handbook of Social Exclusion. doi:ten.1093/oxfordhb/9780195398700.013.0023. ISBN978-0-xix-539870-0. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- ^ Piaget, Jean (1929). The Kid's Conception of the World: A 20th-Century Classic of Child Psychology. New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN978-0-415-16887-8.

- ^ Castelli, Fulvia; Frith, Chris; Happé, Francesca; Frith, Uta (1 Baronial 2002). "Autism, Asperger syndrome and brain mechanisms for the attribution of mental states to animated shapes". Encephalon. 125 (8): 1839–1849. doi:10.1093/brain/awf189. ISSN 0006-8950. PMID 12135974.

- ^ Blanchard, Jay; Mcnincth, George (one November 1984). "The Effects of Anthropomorphism on Word Learning". The Journal of Educational Research. 78 (2): 105–110. doi:10.1080/00220671.1984.10885582. ISSN 0022-0671.

- ^ Dorion, Chiliad. (2011) "A Learner's Tactic: How Secondary Students' Anthropomorphic Language may Back up Learning of Abstract Science Concepts" Archived 18 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Electronic Journal of Science Education. Vol. 12, No. 2.

- ^ Cusack, Odean (2013). Pets and Mental Health. Binghamton, NY: Routledge. ISBN978-0-86656-652-0.

- ^ Aggarwal, Pankaj; McGill, Ann L. (1 December 2007). "Is That Car Smiling at Me? Schema Congruity as a Basis for Evaluating Anthropomorphized Products". Journal of Consumer Enquiry. 34 (four): 468–479. CiteSeerX10.1.1.330.9068. doi:10.1086/518544. ISSN 0093-5301.

- ^ Waytz, Adam; Norton, Michael. "How to Make Robots Seem Less Creepy". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on xiv November 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- ^ Waytz, Adam (13 May 2014). "Seeing Human". Slate. ISSN 1091-2339. Archived from the original on 17 Nov 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

Sources

- Masson, Jeffrey Moussaieff; McCarthy, Susan (1996). When Elephants Weep: Emotional Lives of Animals. Vintage. p. 272. ISBN978-0-09-947891-1.

Further reading

- Baynes, T. S., ed. (1878). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (9th ed.). New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 123–124.

- Mackintosh, Robert (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. ii (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 120.

- Kennedy, John S. (1992). The New Anthropomorphism. Cambridge University Printing. ISBN978-0-521-42267-3.

- Mithen, Steven (1998). The Prehistory Of The Listen: A Search for the Origins of Art, Organized religion and Scientific discipline. Phoenix. p. 480. Bibcode:1996pmso.book.....1000. ISBN978-0-7538-0204-5.

External links

- "Anthropomorphism" entry in the Encyclopedia of Human-Animate being Relationships (Horowitz A., 2007)

- "Anthropomorphism" entry in the Encyclopedia of Astrobiology, Astronomy, and Spaceflight

- "Anthropomorphism" in mid-century American print advertising. Drove at The Gallery of Graphic Blueprint.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthropomorphism

0 Response to "Art of One Age That as So Defined the Characteristics of Human Beings That Is Can Speak"

Post a Comment